AI in Marketing & Branding

Building a Synesthesia Engine with AI (No Code Required)

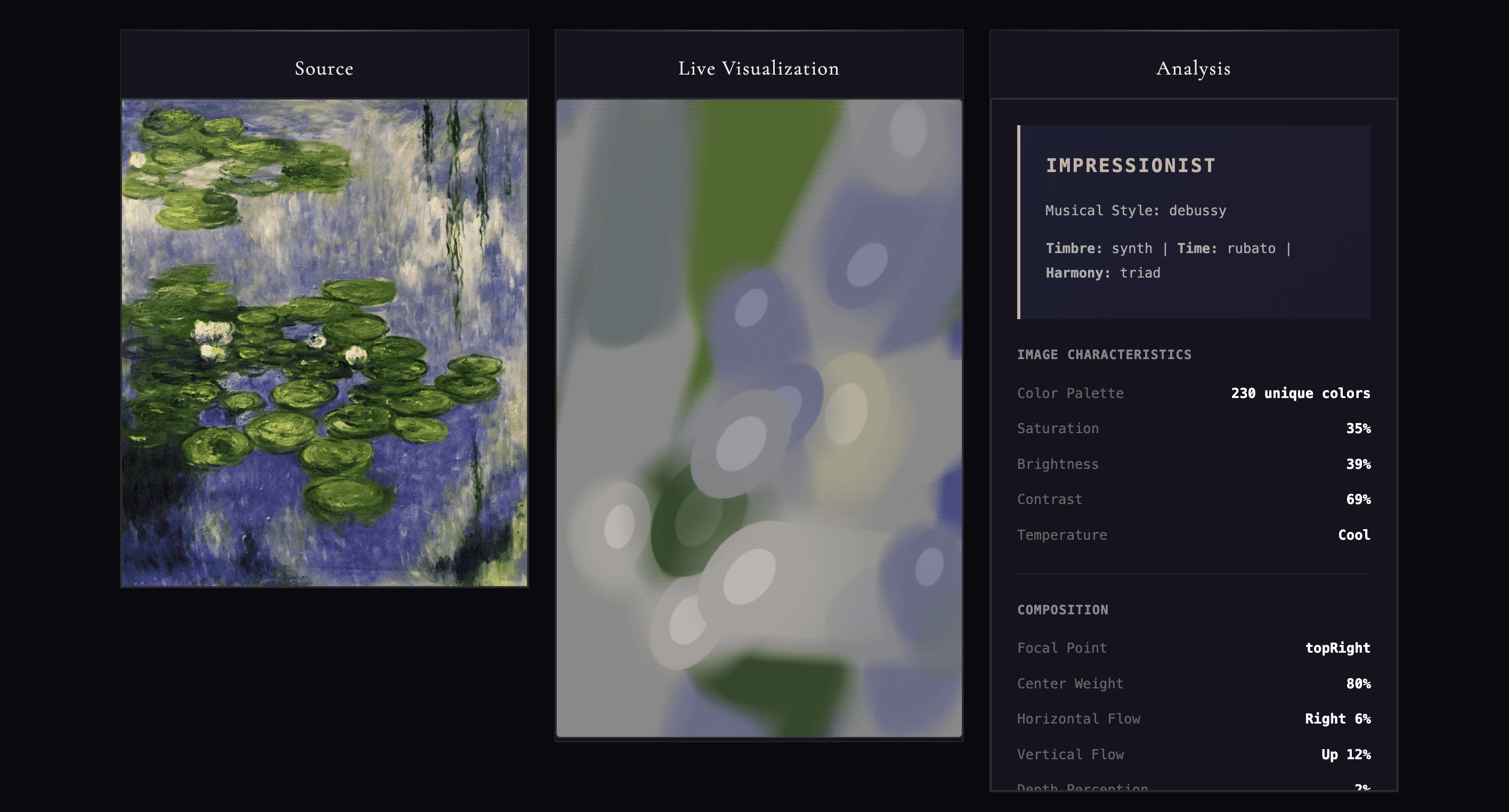

What would a Monet sound like? I used Claude AI to build a tool that translates images into music. No code. Just decades of curiosity and a willingness to try..

When Image Becomes Sound and Vision

Building a Synesthesia Engine with Claude

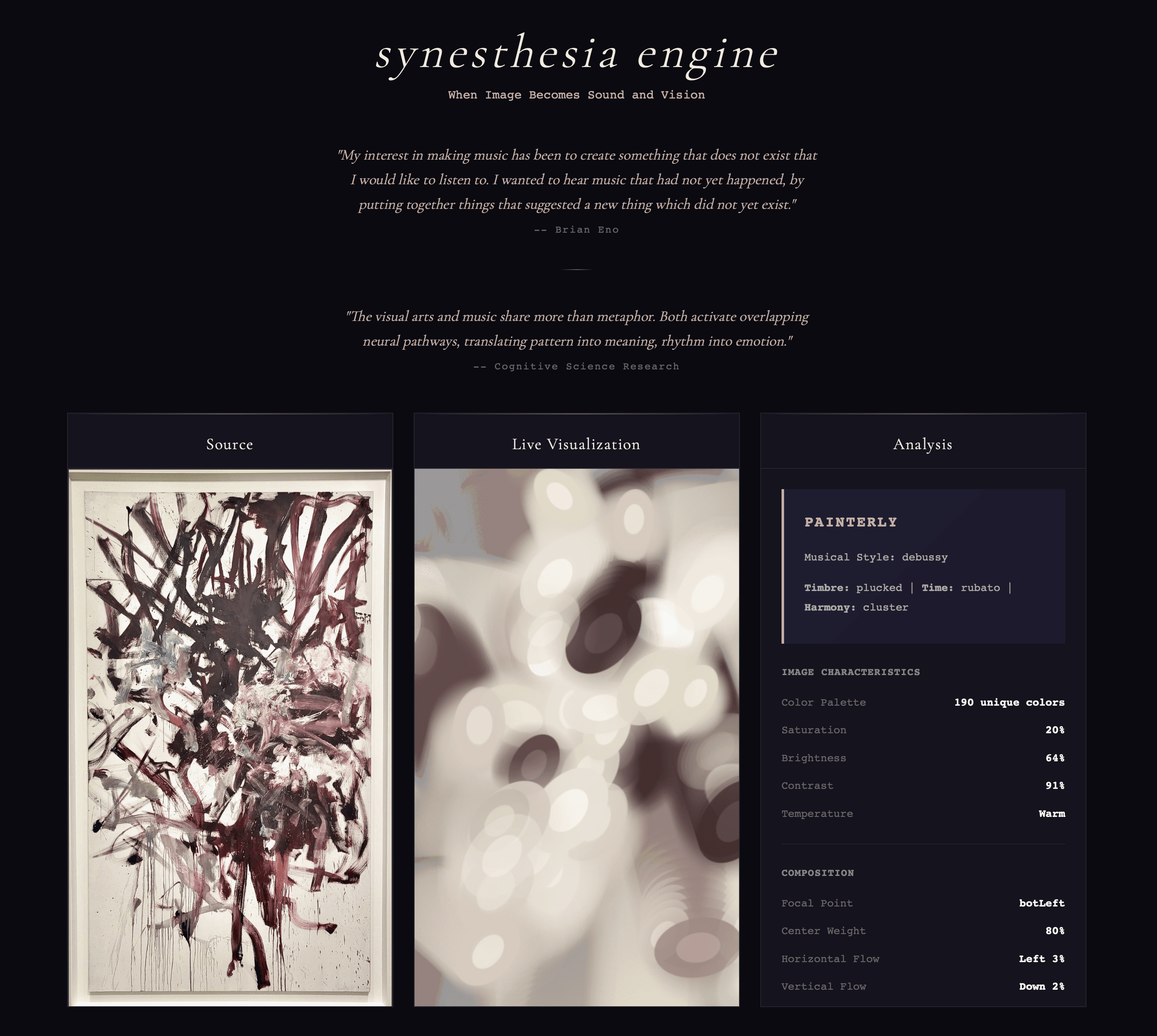

What do you see when you look out at a scenic landscape? What do you hear when you listen to Bach? When you stand in front of a Joan Mitchell painting, is what happens inside you anything like what happens inside me?

I suspect there are similarities but also meaningful differences. And yet, we assume a shared version of reality because we need it to make sense of things. So where do our experiences diverge? Is there any way to share them more directly?

I'm deeply curious about what exists in that space between us. And whether it's not a gap at all, but a universe worth exploring.

The experiment that stuck

When I was twelve, I hooked my Roland keyboard up to my Atari computer using MIDI cables. I figured out how to write a random generator that would trigger notes on the keyboard. I wanted to see if anything other than chaos would emerge.

It didn't. It sounded terrible.

But I was too excited to care. I was watching a computer make music. I was testing if randomness could create something that felt like intention.

That experiment stuck with me. Even then, I knew this line of questioning was something I’d keep returning to, particularly within the intersection of technology and art.

The questions return

Fast forward to this past week. I'm working with Anthropic's Claude on other projects, and that old curiosity resurfaces.

What if we could translate visual experiences into another medium? Not just describe them. Actually translate them.

What would a painting sound like?

Not what music would "go with" a painting. What would the painting itself sound like if it could compose music?

That idea has lived in my head for decades. I just didn't have the technical skills to develop it beyond my imagination. So the idea just sat there. Waiting.

Collaborating with AI

Building with AI tools like Claude means you can describe your ideas and the AI will build them. I didn't write a single line of code, but I directed, I reviewed, I provided feedback, and I asked questions. I knew what was wrong before I could explain why, and I kept going until the system began to align with what I had in my head.

Claude's first attempt was a generic tone generator. It analyzed some image features and produced sound. Technically impressive, especially compared to what was possible a few years ago. But boring. Every image sounded basically the same.

"Everything sounds the same, and it sounds bad. Explain to me how you're establishing the parameters and variables."

Claude explained and tried again. Added seventeen parameters. Scales, chord progressions, rhythm patterns, and melodic algorithms. Very sophisticated. Still sounded the same. Still horrible.

"You're feeding different data into the same machine," I said. "Let the variety of the inputs express itself as richly as the outputs, but with structure and logic that gives it form."

That's when things got more interesting.

Divergence, not just variation

The problem wasn't a lack of parameters - it was convergence. All paths led to the same synthesis. Same instrumentation, same texture, same sonic world. AI gravitates toward safe averages. You have to push it to truly diverge.

So we rebuilt from scratch: five distinct sonic profiles based on image type. Different timbres, different rhythms, different sonic worlds.

It worked.

Until I uploaded a Monet.

When beautiful sounds eerie

The system was generating five distinct sonic worlds. Technically, it worked. But the dissonance created somewhat unpleasant-sounding results that seemed to clash with the "feeling" of the image.

I uploaded a Monet painting of water lilies, all blues, greens, and purples, with lush Impressionist brushwork. Beautiful. Dreamy. Romantic.

It sounded like a horror-movie scene where the main character makes the always-wrong decision to venture into the dark basement.

"Why does this sound creepy?" I asked Claude. "This is Monet. This should sound beautiful."

When you translate between fundamentally different languages - visual to auditory - there will be inevitable friction. Dissonance. Unexpected results. The system is making thousands of decisions per image: which frequencies, intervals, timbres, and timing. Some of those decisions work. Some don't.

A note on building with AI

Something worth knowing about "vibe-coding" with today's AI tools: the first version is almost always bad. You need to know when to start over rather than refining on top of flawed foundational logic.

My advice is to always ask about the fundamentals the AI is developing around. Otherwise, you risk wasting time watching it fail for reasons it can't see because it's looking at the wrong problem.

A few years ago, the Monet moment is where this project would have died. I'd have no way to act on the instinct that something was structurally wrong. Now I just said it out loud and watched it happen.

The gap between us

I can't actually know what you hear when you look at a Monet. I can only make culturally-informed guesses. Impressionism often feels like Debussy. Textured and flowing and romantic. But maybe for you it sounds like jazz, or silence, or something that doesn't exist yet.

The synesthesia engine can't translate your experience to mine. It can only create artifacts that let us explore the space between our experiences.

When you upload an image and hear what the system generates, you're not hearing "the truth" of that image. You're hearing one possible translation, built on shared artistic context and music theory. You might think "yes, that feels right," or "no, that's completely off," or "hmmm, I never thought of it that way."

And in that reaction, that moment of recognition or disagreement, we catch glimpses of each other across the gap. We can't close it. But we can look into it together.

The intelligence underneath

Even with divergent sonic worlds, something still felt too arbitrary. So we built deeper connections. The visualization pulls actual colors from the image by frequency. Pitch controls speed. Higher notes move faster. Rotation follows the dominant edge angles in the painting. Delay ties to saturation. Vivid colors appear instantly, muted ones fade in. Every visual element listens to both the music and the image, translating between them.

What this is really about

This isn't just a toy. Although, to be fair, it is a toy. You upload an image and watch colored shapes dance to music generated from that same image. That's delightful.

But underneath, it's about the questions I've been asking since I was a child. Can we translate experience? Can we build bridges between different ways of perceiving?

The answer is yes, and no.

Yes, we can map properties. Frequency to speed. Color to palette. Texture to timbre. We can try to build systems that recognize aesthetic context, that understand impressionism should sound different from pop art. Sometimes it works. Sometimes a Monet sounds lush and romantic. Sometimes it sounds like a horror movie scene. The system makes thousands of assumptions, and some land better than others.

But no, we'll never translate your experience to mine. That gap remains. And honestly? The failures are as interesting as the successes. When something sounds "wrong," that tells you something about the assumptions baked into the system. And about what you expected to hear.

The synesthesia engine doesn't solve for the gap. It just makes it visible. Makes it something we can play with and explore together.

Try it yourself

You can play with it here. Upload a painting, a photograph, or a drawing. Any image. Watch what happens. Listen to what happens.

It won't tell you what I see when I look at your image. But it might show you something you hadn't seen before. And it might open new ways of thinking about how we experience the world, and how art helps us reach across the spaces between us.

*******************************

Technical note for the nerds: I built this with Claude, not by writing code, but by knowing what I wanted and refusing to accept less. The technical details below are real. I just didn't have to be the one who wrote them.

Built with vanilla JavaScript and the Web Audio API. Image analysis extracts color palettes, edge angles, texture variance, spatial distribution, and compositional focal points. Aesthetic categorization uses threshold combinations (e.g., texture + saturation + softness for impressionist detection) to identify artistic contexts, then maps these contexts to appropriate musical styles using sound theory. Each aesthetic gets its own scale (pentatonic, whole tone, mixolydian, Phrygian, etc.) and chord voicings (9ths for Debussy, suspended for ambient, triads for classical). Everything runs client-side. No backend. No data collection. Just you, your image, and a system that's actually trying to understand what kind of art it's looking at before deciding how it should sound.